Students voice varied opinions on the Pledge of Allegiance in public schools

The Mav interviews students about the topic of an upcoming opinion series

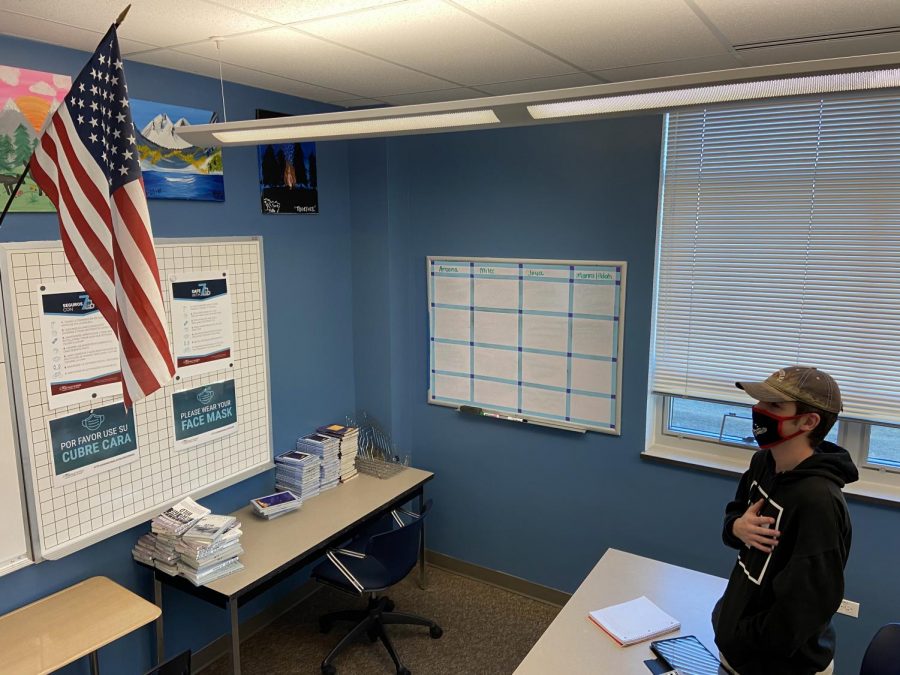

The Mav is currently working on a three-part series on the topic of whether or not the Pledge of Allegiance should be recited in public schools. This series will include the perspectives and personal opinions of two journalists from The Mav newspaper debating why their position is correct based on three different topics: whether the recitation of the Pledge is constitutional or not, whether it is respectful or disrespectful to veterans, and whether it aligns or does not align with particular religious values. With this series coming up, we wanted to share multiple student perspectives on the topic. We had the opportunity to interview five students: three who believe the Pledge should be optional and two who believe the Pledge is an important matter of respect and honor.

The argument about whether or not students should recite the Pledge is not new. With news coverage ranging from Colin Kapernick kneeling during the National Anthem to students being asked to leave classrooms (in Boulder County Schools) for not saying the Pledge, the subject matter is still worth considering today.

Vinny Purrier (‘21) said, “The Pledge of Allegiance is a choice. My First Amendment right states that I can and should be able to decide whether or not I stand or even say the Pledge.”

However, students who choose not to stand explain that they have felt social pressure to do so, some claiming they experienced disrespect from their peers.

Purrier shared that he personally experienced episodes of “verbal disrespect” when he was younger but that it has now dissolved into “nasty looks” from students across the classroom.

Petra Jensen (‘23) also shared with The Mav that she, too, has experienced disrespect in the classroom for actively choosing not to stand (or say) the Pledge of Allegiance when it is broadcasted over the intercom.

But not all students believe they have been subject to glances or judgement for their stance.

Jordan Wagner (‘22) said, “I myself have not gotten any disrespect for not standing for the Pledge.”

Some students that choose not to stand believe reciting the Pledge routinely is a violation of the Constitution. They argue that soldiers fought for their freedom not to stand and that the First Amendment (which protects freedoms of religion, assembly, protest, speech, and expression) guards their refusal to stand for the Pledge.

Others believe it is an issue of disrespect toward veterans who have served or are currently serving.

Teagan Rodgers (‘22) agrees with the point that the Pledge honors veterans. He said, “I stand because of the sacrifices of the men and women who fought for the country and died.”

Jensen (‘23) said that in her opinion, the Pledge “has no correlation” with veterans. They are separate forms of patriotism, according to her.

Jordan Wagner (‘22) agrees with this sentiment. She also feels neutral, explaining that the Pledge is more connected with America’s ideals and America as a whole rather than veterans.

This is why she has chosen not to stand for the Pledge in the past as she doesn’t “like how [President Trump] and his supporters [have treated] the Black Lives Matter movement, police brutality, and how [Trump] has approached handling COVID-19”. Because she thinks that the Pledge embodies what’s happening in America, she believes she should choose when to stand or not based on current events.

Purrier (‘21) said that though the Pledge itself isn’t disrespectful, making it socially unacceptable and abnormal to reject standing for the Pledge “clearly disrespects the tenets our veterans fought for”. He explained that veterans fought against forced patriotism and for freedom of choice.

But for many, the connection between the Pledge and veterans is deeply personal. Many citizens of the United States have ancestors or current family members who served in the military.

“I cannot fathom the amount of blood, sweat, and tears that have been shed for that flag, and for this country, and for my freedom. I [stand for the Pledge] out of my respect for those who sacrificed things for it and my love for my country and what it stands for,” said Lauren Fehrn (‘24). The Pledge is especially meaningful to her because her father and other family members are veterans.

Many children are taught the Pledge of Allegiance at an early age. Some say that children in elementary school (and in some cases younger) are taught to memorize the Pledge before they are capable of understanding its meaning.

Most of the students we interviewed agree that the history of the Pledge isn’t being taught as much as the words are.

Wagner (‘22) said, “Most people don’t learn the history of the Pledge until later on in their lives.”

On the other hand, Purrier (‘21) said, “Teaching the Pledge is fine. I see no issue with simply teaching children what the Pledge is. The same way I see no issue with teaching children the National Anthem.” He said that the Pledge only becomes an issue “when it [is] expected that children say it every morning, even if they don’t fundamentally agree with the [opinions mentioned] in the Pledge”.

While some feel strongly about whether standing or not standing for the Pledge is an issue of respect, others are concerned about the religious implications.

Wagner (‘22) said, “I believe it is an establishment of religion because the original Pledge did not have ‘under God’ in its lyrics. ‘Under God’ was added in 1954 because of the communist threat in America at the time.”

The argument that opposes this is that the Pledge is not an establishment of religion. Some students believe that it is not an actual establishment of “God” but is talking about our “God-given” rights.

Also, some students say perhaps those who added the word “God” to the pledge didn’t mean one specific god. They very well could have been saying that all religious beings and supreme beings are protecting this country, which means whatever you believe in is protecting you.

Ferhn (‘24) said, “The phrase ‘under God’ doesn’t necessarily have to insinuate any religious connotation. It’s basically saying that we are all under something greater than ourselves that is not a government.”

The Mav does not want to editorialize (add our opinion in a news feature), but we believe it is appropriate to end with this: it is our job, as Americans, to be part of civic conversations that allow for multiple perspectives to be shared and considered. We look forward to our readers engaging in our series on this topic. The full series will be published next week on Wednesday, March 3.

UPDATE: All of the opinion articles are now published! Click here to read the first part, here to read the second part, and here to read the third part.

Your donation will support the student journalists of Mead High School. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.

Ryan Dallas is a Senior. He enjoys watching movies and tv shows, writing, and hanging out with friends. He is excited more than ever to write movie reviews as well as broaden his journalistic abilities.

Alex Olson • Feb 26, 2021 at 4:59 pm

Very thorough and interesting look at student’s opinions on standing for the pledge. I’m looking forward to reading the rest of the series.

Rachel Sandoval • Feb 24, 2021 at 7:39 pm

Nice work and great writing. I love the last paragraph.

Rachel Long • Feb 24, 2021 at 2:49 pm

I like how you provided different viewpoints on why or why not students choose to stand for the pledge. I think this is a fair, well-balanced article on a very controversial subject. Good job Ryan and Mav team!