*Opinion articles are the views of the writer(s) themselves and do not represent an official stance of the student newspaper, Mead High School, or the Saint Vrain Valley School District.

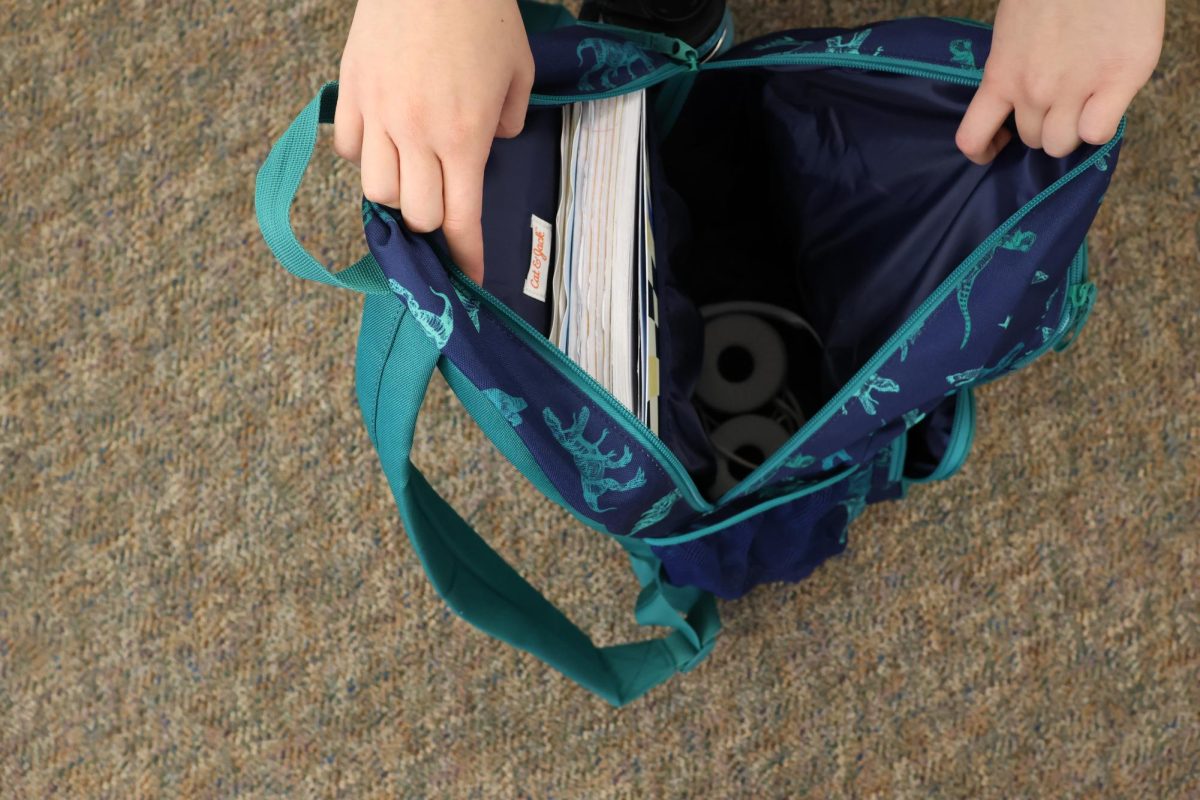

Imagine coming into school for another day of class. An assistant principal comes into the classroom, pulling you into his office. He tells you that he has a report that you are carrying ibuprofen, which is against school policy. You agree to let him search your bag, which is not enough for the staff, who then proceed to strip search you, finding nothing.

As a student, this real situation is concerning because it invalidates student privacy rights in the United States. In the modern era, the only words that separate your rights to privacy and school officials being able to search you and your belongings are two words: “reasonable suspicion.”

Reasonable suspicion is both a subjective standard and violates Fourth Amendment rights.

Firstly, let’s look at what the standard is here at Mead High. Mead High is required to comply with district policy. St Vrain School District searches must be conducted under the following regulations: the “principal or designee… [has] evidence that the student has violated or is violating laws or school rules[;]… [admin] may search a student [or their] property while on school premises[; admin] may seize any illegal, unauthorized, and contraband materials”.

Reasonable grounds are based on facts provided by a “reliable informant or personal observation.” This means that a school official can search a student based on another peer that may have a biased view of said student.

When a police officer searches someone or their belongings, the cop has an immediate and reasonable interest in doing so—such as witnessing someone assaulting someone, or seeing evidence in plain view. The courts generally prohibit cops from searching or seizing something without a warrant supported by probable cause, unless there are compelling reasons for doing otherwise.

However, the Supreme Court has carved out broad exceptions, called the “special needs doctrine,” under which the public education system falls. It has carved out these exceptions in certain cases, such as international airports, the border, prisons, and schools.

The Court ruled in New Jersey v. T.L.O., that despite the “legitimate expectations of privacy” that students have, the school has an “equally legitimate need to maintain an environment in which learning can take place.” This means that restrictions on school access to students’ privacy can be eased. Students are not held to probable cause and do not need a warrant to search.

Mind you, the “reasonable suspicion” standard was established to prevent armed criminals involved in crimes to be stopped and frisked for dangerous weapons(Terry v. Ohio). It established that the government has a compelling reason to search certain individuals under specific circumstances. However, this standard is being applied to the school system, and that’s where it becomes problematic. At first glance, it seems reasonable. However, there are several glaring problems.

In virtually every high school curriculum in the nation, students are taught about the constitutional rights which Americans are entitled to under the Bill of Rights. The standard set by Tinker v. Des Moines has allowed students throughout the country to symbolically engage in speech through art or clothing, and it’s inspired State governments to enact laws specifically protecting the rights of student journalists.

Something is still lacking in constitutional rights in public schools. Despite the fact that the Fourth Amendment is just as applicable to the public education system, the courts have gutted privacy protections for students.

And this is where the constitutional standards in school become arbitrary. We recognize freedom of speech and the right to privacy as some of the most basic rights which Americans are entitled to, however; the Court has ruled that while schools have no reason for restricting speech which is not disruptive, it simultaneously holds that schools do have an interest in restricting privacy rights, even if there is no objective reason in doing so.

In fact, in their dissenting opinion in the New Jersey v. T.L.O decision, Justices Stevens and Marshall make a similar point, saying that a search or seizure could be considered reasonable under the provisions of the Fourth Amendment, provided that “they have reason to believe that the search will uncover evidence that the student is violating the law or engaging in conduct that is seriously disruptive of school order, or the educational process”. This standard would protect student’s Fourth Amendment rights on the same basis as their First Amendment rights, excepting cases where a student may be violating the law. Although the standard given by the dissenting Justices still allows for the reasonable suspicion to be applied to minor crimes, it would be significantly better than our current standard.

It is arbitrary and unreasonable to deny students basic privacy simply due to the subjective opinions of public school officials and the courts, especially when there are ways in which the two interests could be balanced in a way that is more equitable for students.

The Court, in the decision Safford Unified School District v. Redding (previously mentioned) ruled that regarding the strip search for ibuprofen, the “petitioners Wilson, Romero, and Schwallier are protected from liability by qualified immunity because ,“clearly established law [did] not show that the search violated the Fourth Amendment”. This set a precedent that even if a search is held unconstitutional, the officials engaged in that search can not be held accountable for their actions. If another violation of basic privacy rights were to occur again, the officials who would be ruled to have violated the Fourth Amendment would not be subject to liability.

Under the current standards, the only official who can be held accountable for Fourth Amendment violations are those who engage in a strip search without reasonable suspicion, an incredibly low standard to hold our public officials accountable to.

One may say that this issue is of minimal concern or importance because the opinions and rights of teenagers are not important. That could not be farther from the truth. At this time in our lives, students are at their most vulnerable. Not only are searches a generally undignified affair that can be considerably traumatizing, the outcomes of those searches can drastically affect someone’s life. Our schools have no business treating any student on the same basis as criminals and terrorists, simply because it makes their job easier. They are subject to the Constitution, and to the same ethical standards as everyone else. Despite defying common sense, human rights, and the law, schools continue to use this standard. It’s long time to change that.